Storytellers for children: Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru birth anniversary: The former Prime Minister wrote several books that have been lauded as records of his life, the freedom struggle and an explication of his vision for independent India.

(This is the second in a series on iconic storytellers for children.)

By Deepa Agarwal

Jawaharlal Nehru’s love for children is so legendary that his birthday, November 14, is celebrated as Children’s Day. Chacha Nehru, as he was affectionately addressed, felt that like flower buds in a garden, children should be carefully and lovingly nurtured, since they were the future of the nation and the citizens of tomorrow. For him, children were the real strength of a country and the very foundation of society.

This philosophy is amply demonstrated in the letters that he wrote to his daughter Indira Gandhi when she was a young girl, which were later published as books.

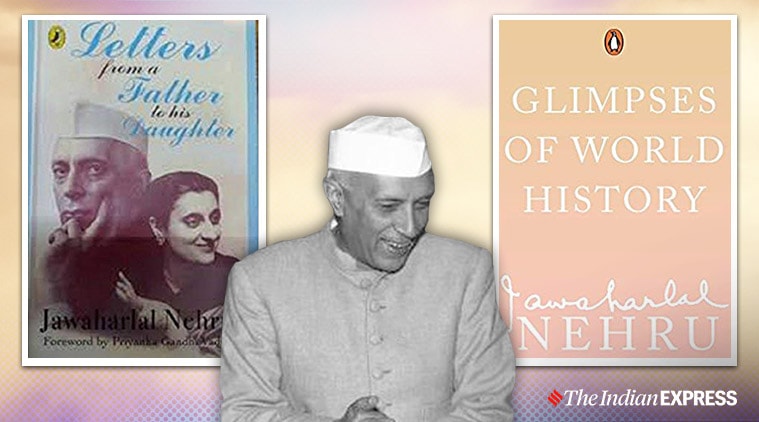

Nehru wrote several books that have been lauded as records of his life, the freedom struggle and an explication of his vision for independent India. Among these, Letters from a Father to his Daughter and Glimpses of World History have become popular children’s classics because any child can respond to their warm, affectionate tone and his lucid and spontaneous style. The wealth of information woven into them and his unique approach to historical facts is an added bonus. Again, when personal letters are published as books, the reading experience becomes an engaging one-to-one dialogue. And when it is the first Prime Minister of our country writing to his daughter, also a future Prime Minister, curiosity naturally escalates.

Letters from a Father to his Daughter is a series of letters written in 1928 when Indira Gandhi was almost 10 years old. She was spending the summer in Mussoorie and Nehru was in Allahabad. This distance denied them the opportunity for their usual conversations, so he bridged it through letters containing “short accounts of the story of our earth…” And what a story it turned out to be! Beginning with “The Book of Nature”, Nehru traverses the entire course of evolution-the coming of man, the development of civilisations, the institution of kingship and finishes with a description of the two great epics, The Ramayana and The Mahabharata and their significance, ending “…they live today in India and every child knows them and every grown up is influenced by them.” This book provides us with deep insights into the father-daughter relationship and indicates how important it was for Nehru that his daughter grow up with comprehensive knowledge and understanding of the world she inhabited.

Glimpses of World History is a compilation of letters written in different circumstances, begun while he was in Central Prison, Naini in 1930. It is a vast tome of 1155 pages, not really a book to be read in one sitting but to be taken a few chapters at a time. While Letters… is more impersonal, with the focus on sharing information, in Glimpses… an intimate note creeps in with accounts of life in jail, his hopes and aspirations for the country he loves, his political philosophy and most poignant, his anxieties about his family.

Jawaharlal Nehru: Know more about India’s first PM with these children’s books

The situation in 1930 was far more heart-wrenching indeed. Father and daughter were a short distance from each other, but the high prison wall separated them. Indira was older -turning thirteen, and the first chapter is titled “A Birthday Letter for Indira Priyadarshini on her Thirteenth Birthday”. Considering the times, remarkably, Nehru never talks down to his daughter. In fact, he proclaims: “You know, sweetheart, how I dislike sermonising and doling out good advice.”Also, “A letter can hardly take the place of a talk; at best it is a one-sided affair. So, if I say anything that sounds like good advice do not take it as it were a bad pill to swallow. Imagine that I have made a suggestion to you for you to think over, as if we were really having a talk.”

These words set the tone for a ramble through the course of world history, punctuated by Nehru’s views on a variety of topics. He uses examples from history to illustrate his opinions, as well as lessons from the natural world, like that of insects. The cycle of history, the rise and fall of nations and civilisations-India, Egypt, China, Greece and elsewhere, preoccupies him-the wheel of change as he calls it. While pondering over the dynamism of the European personality with its desire to conquer and colonise, he emphasises the continuity of civilisation in India and China, not forgetting that we are “heirs of the good and bad”.

Nehru’s belief that the concerns of the whole world are more important than those of a single country provides an insight into his pluralistic vision and all-embracing philosophy. As he rightly states: “But history is one connected whole and you cannot understand even the history of any one country if you do not know what happened in other parts of the world.”

His strong leaning towards socialism crops up again and again when he condemns social injustice and dwells upon the transitory nature of greatness. When he reminds Indira that she was born in 1917, the year of the great Russian Revolution, we get an indication of his future policies. He connects it with our own revolution, mentioning his exhilaration on hearing shouts of “Inquilab Zindabad” from within the prison. On the other hand, the chants of “Ganga Maiyyaki Jai!” as pilgrims make their way to the Magh Mela at the Triveni Sangam, remind him of the suffering of the masses.

Nehru states that the cause of humanity is greater than anything else. But there are touching glimpses of the trials of incarceration because family visits and letters are restricted. His anxiety about his wife Kamla, also in prison and his ailing father are shared too.

Nehru doesn’t trouble himself with dates, but connects past with present by informing Indira that the sage Bharadwaj’s ashram existed not too far from their home at Anand Bhawan. Along with the glimpses of history, you receive glimpses of his vision for the new country as one thought or topic sparks off another in a constant flow of ideas.

His optimism and belief that change will come are evident, in statements like: “In India today we are making history, and you and I are fortunate to see this happening before our eyes and to take some part ourselves in this great drama.”

Thus, while making history, as a conscientious father, Nehru tried to shape Indira’s worldview and broaden her outlook. For this reason, these letters remain as relevant today by fulfilling an essential purpose of children’s literature – communicating humanist values.

(Author, poet and translator, Deepa Agarwal writes for both children and adults and has over 50 books to her credit. She interacts regularly with children, conducting creative writing workshops and storytelling sessions in schools. She tweets @dipuli.)

Source: Read Full Article