Puu, a children’s book on manual scavenging, was born of ‘anger’

While manual scavenging has been officially prohibited by law in India since 1993, instances of the dehumanising practice continue to be recorded, due to its deep-seated roots in society. Sensitively written, children’s picture book Puu is about a little girl who faces discrimination at her school because of her parents’ occupation. “Most people ignore me. It’s not like I care,” says the child in the book.

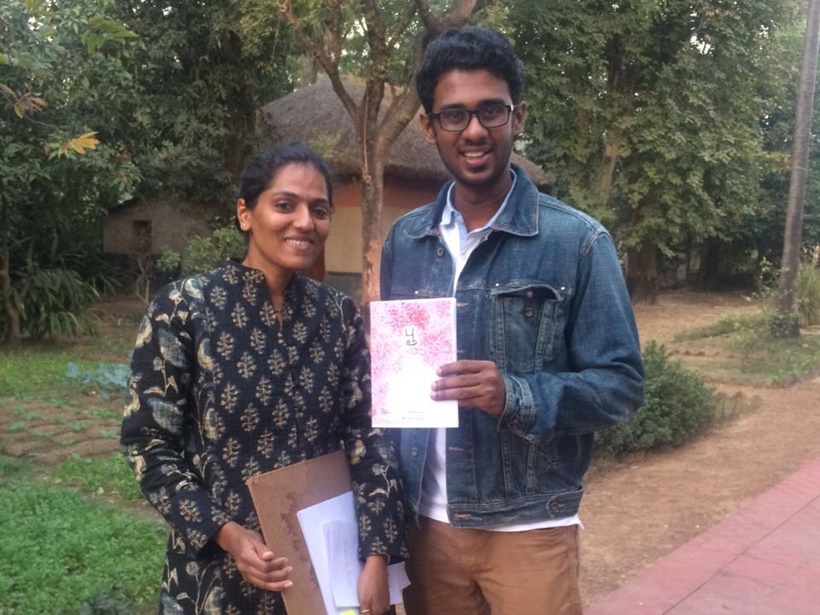

C G Salamander, who has also authored Tara’s Elephant, Ramya’s Snackbox, Palm’s Foster Home for Peculiar Stories, talks about his book, illustrated by Samidha Gunjal and published by Scholastic India.

Why did you choose to write on manual scavenging?

A few months after my board exam, during a trip, a friend of mine used a train toilet and came back convinced that any waste exiting the train shrivelled to dust before it hit the tracks, on account of the speed of the train. This, of course, was ridiculous. He was shocked to learn that people were employed to pick the excrement up, especially in railway stations after the trains came to a halt.

That was the first time I actually thought about manual scavenging, and it made me angry. I was angry that I hadn’t seen it before; it was happening all around me and somehow I hadn’t seen it; I had refused to see it. As adults, we’re desensitised and we’re more prone to making excuses for social inequalities; we speed-walk past men submerged in sewers, we un-see the women who clean the train tracks. Children aren’t like that; they have a greater sense of outrage when it comes to injustice. They ask difficult questions and when they hear about something as dehumanising as manual scavenging, they react the right way—they’re angry. That’s why I chose to write a children’s book on manual scavenging.

The book is on manual scavenging. You have addressed it subtly by using flowers to tell the story. What prompted that?

We knew we had to use a metaphor because it would have been far too cruel to have our character pick up a realistic representation of excrement; we would never do something so inhumane to our character. We also didn’t want to use garbage or show a junkyard because we wanted the focus of the book to be on manual scavenging, and not rag or waste picking. The reason we used flowers is because the Tamil word Puu (meaning flowers) sounds a lot like an English word that means something completely different. It was the perfect metaphor.

In the book, the little girl feels ignored by her friends and says that she doesn’t understand why and doesn’t care. How are you hoping kids will react to this?

With a pang of sadness, followed by a flood of empathy.

Could you comment on the trend of children who are involved in the practice, along with their parents? Are there any stats that you would like to share?

In July 2014, parents from the Valmiki community in Ratanpur village Gujarat, confronted teachers and school authorities after finding out that their children were made to come early to school and clean toilets. They were beaten and chased away, and on the very next day, the children of the manual scavengers were physically punished for complaining.

Let’s get one thing straight, there isn’t a parent in the world who would want their child to become a manual scavenger. It’s caste discrimination—be it in the form of education or employment—that forces the offspring of manual scavengers into the practice. The Navsarjan Trust compiled a document, with compelling stats, from interviews with 1,048 children (age groups 6 to 17) in Gujarat. You’ll find quotes from children talking about their discrimination and how it has led them to engage in this inhumane practice. I think it’s important for people to go through the document themselves, that way we see children as children and not numbers.

This book was conceived at the Goethe Institute’s Children Understand More workshop. Do you believe children show more empathy towards such issues?

Absolutely! That’s exactly why Puu is a picture book for children. We believe that children aren’t as desensitised as adults, and are thereby less resigned to accept the world the way it is.

What has the reaction been to the book? Any interesting responses from young readers?

So far, it’s been well received. It’s fun to watch children read the book and then piece things together. Our favourite reaction is when children ask us what they can do to help and stop manual scavenging. The most interesting response, however, is my neighbour who wanted to know where he could get a pet pig.

You have used fewer words and more illustrations to get the message across. Do you think picture books have the power to communicate powerful ideas? Any other examples of such books?

My favourite thing about picture books and comics is that the reader makes the story up along with the writer and illustrator. For example, if I were to show you a picture of an archer aiming at a large red balloon, and then a picture of red balloon scraps on the ground, your mind automatically fills in the gaps with visuals of the balloon being shot. This is something that only graphic narratives can do. They have the power to make their readers crucial to the story, and reader involvement is key when you’re conveying a powerful idea.

There are a few Indian picture books that come to mind, particularly the ones that deal with disabilities. Another story that I’m excited about is Pratham Story Weaver’s forthcoming picture book which features a transgender protagonist. But if I’m being honest with you, a lot of the books that answer your question exist as manuscripts or are being worked on as we speak. Perhaps they see the light of day, or maybe they won’t. Only time will tell.

Source: Read Full Article